Emily Cullen is a Galway-based poet, scholar and harper. She was awarded an Irish Research Council fellowship for her doctoral study in English at NUI Galway. Emily has performed internationally with a variety of music ensembles including Galvia, The Belfast Harp Orchestra, Ceoltóirí Maghlacha and The Cullen Harpers (with her three sisters). She has also recorded on a number of albums, such as the Grammy award-winning Tribute to the Celtic Harp with The Belfast Harp Orchestra and The Chieftains, and she gives recitals, workshops and lectures throughout Europe, North America and Australia. Emily teaches part-time at NUI Galway and is the author of two poetry collections: In Between Angels and Animals (Arlen House, 2013) and No Vague Utopia (Ainnir Publishing, 2003).

Emily Cullen is a Galway-based poet, scholar and harper. She was awarded an Irish Research Council fellowship for her doctoral study in English at NUI Galway. Emily has performed internationally with a variety of music ensembles including Galvia, The Belfast Harp Orchestra, Ceoltóirí Maghlacha and The Cullen Harpers (with her three sisters). She has also recorded on a number of albums, such as the Grammy award-winning Tribute to the Celtic Harp with The Belfast Harp Orchestra and The Chieftains, and she gives recitals, workshops and lectures throughout Europe, North America and Australia. Emily teaches part-time at NUI Galway and is the author of two poetry collections: In Between Angels and Animals (Arlen House, 2013) and No Vague Utopia (Ainnir Publishing, 2003).

Anatomy of a Genius

By Emily Cullen

Flash fiction for Halloween. (Inspired by real events which took place in Cambridge in 1768)

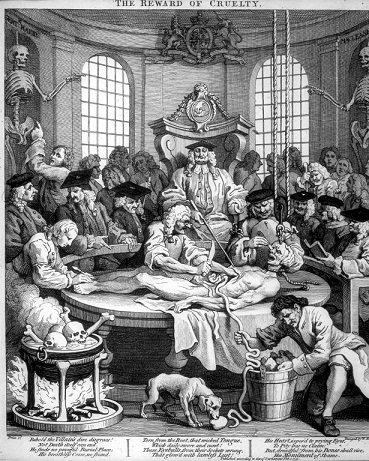

We crane our heads round the table, beneath the skeleton that dangles like a marionette. Our talk of politics ceases as Prof. Collignon pulls back the sheet.

The stench of death is pungent, but I must not flinch. I palm the handkerchief in my pocket, fighting the urge to cover my nose. Le Prof nods to the anatomist, who orients the knife towards the abdomen.

I’m assailed by sudden nausea. Could it be ….? My mind returns to the Sir Reynolds portrait. That large nose … curvature of the mouth; unmistakable – it is he …. undoubtedly!

“Hold your knife Sir. I know this man,” I motion to the surgeon. “It is old Yorick himself!”

A collective gasp from the group. There before us, upon the cold slab, lies the corpse of the great Lawrence Sterne: author, satirist, man of the cloth.

“Who is zis man exactement? asks the Prof.

“Monsieur, this is our English Rabelais, if you will, author of the ribald Tristam Shandy.”

“Wish I had his brilliance,” one of junior students offers, in a cadence of resignation.

“Should we not examine his brain, rather than his abdomen, whilst we have this uncommon opportunity?” pipes up another. “Forget your phrenology, gentlemen”, he adds, “a true genius lies before us.”

A fleeting look of horror gives way to one of calm questioning on our faces.

“How will the cranium of an author differ from those of the wretched villains we have seen?” I pose, sensing I’m already defeated.

“This is precisely what we shall discover today.”

There is a low hum; a pregnant pause.

“Would that be of sound … ethic, sir?” my good friend, Charles interposes, raising his eyebrows at me.

“We are fortunate that Mr. Sterne is at our legitimate disposal. We could,” the anatomist pauses, “make a discreet incision, then return him to his place of rest. After all, it is in the interest of science.” He remains composed. Knows he will receive our student shillings for this dissection.

A lengthy hesitation follows. We are complicit by our silence; could slice the proverbial air with our scalpels.

“If this is agréable to all, we shall proceed with a craniotomy.”

My heart is pounding behind my breast bone. The surgeon lays down his knife. He grasps his saw, begins to cut into Sterne’s crown until he reaches the cerebral cortex.

All of a sudden, he jolts backwards. Wondrous, spectral figures emanate from the gaping lesion, floating high above our heads. They drift round the theatre, some of them just about discernible: the outline of Ireland, a parson’s acoutrements and wig, rows of spines and thick tomes upon shelves, a pantheon of giants, such as Plato, Socrates and Swift.

A small ball of golden light swirls around us like an Alice Wheel. It becomes too bright for our eyes. Terror gains ascendancy over the awe in our faces. We raise our hands to block out its beams, edging backwards towards the walls.

“Seal the wound! Now!” one of the students commands.

The anatomist cups the cadaver’s head between his hands; prises the perforation back together. With a trembling hand, he sutures the putrid flesh.

The phantoms and orb of light evanesce. The theatre fills with an uncertain glow as the shadow of a skylark crosses the hall and disappears.

Audible sighs mingle fear and perplexity with relief. We remain stunned….paralysed.

“Resurectionistes!” the pallid professor eventually blurts. “They dug into his grave. I paid ‘zem. But, of course, it is no crime to excavate a body; only theft is beyond the law.” He is trying to assuage his remorse.

“We must return him to St. George’s at once!” I instruct, in a tone of finality.

And so we do, that very night. And as we lower him back into his rightful place in the earth, under the moonlit gloaming of the bell-tower, we vow never to speak of the soul science has squandered this day.

Note: In this curious case of life imitating art, ‘Yorick’ is the name of the dead court jester whose skull is exhumed by the gravedigger in Act 5, Scene 1, of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Coincidentally, the name was used by Laurence Sterne in his novels Tristram Shandy and A Sentimental Journey as the surname of one of the characters, a parson who is a humorous portrait of the author. Indeed, Parson Yorick is supposed to be descended from Shakespeare’s Yorick.