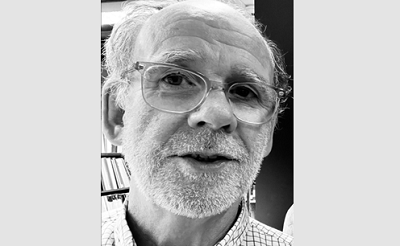

John Coburn is an Anglo-Irish poet living in London. In collaboration with Peter Fallon (Gallery Press) and Trevor Scott (Dun Laoghaire School of Art) in the 70s, he founded the short-lived Rainbow Manuscripts, publishing Brendan Kennelly and Jim Burns with design by Niall O’Neill and Catherine Ryan. Early work appeared in Grapevine Magazine, Sunday Independent, Poetry Almanac’s Autumn Anthology and has been broadcast on RTE. Retired from a career in IT working in Europe and the Middle East, recent work has appeared in Atrium, A New Ulster, Black Nore Review, The Broken Spine, Causeway/Cabhsair, Eunoia Review and Ink Sweat & Tears.

John Coburn is an Anglo-Irish poet living in London. In collaboration with Peter Fallon (Gallery Press) and Trevor Scott (Dun Laoghaire School of Art) in the 70s, he founded the short-lived Rainbow Manuscripts, publishing Brendan Kennelly and Jim Burns with design by Niall O’Neill and Catherine Ryan. Early work appeared in Grapevine Magazine, Sunday Independent, Poetry Almanac’s Autumn Anthology and has been broadcast on RTE. Retired from a career in IT working in Europe and the Middle East, recent work has appeared in Atrium, A New Ulster, Black Nore Review, The Broken Spine, Causeway/Cabhsair, Eunoia Review and Ink Sweat & Tears.

I Was A Fenian Blacksmith

“Some died by the glenside, some died near a stranger

And wise men have told us their cause was a failure…”

‘The Bold Fenian Men’ – Peadar Kearney *

From the empty ancient fields I return

with my new pikes unbroken – barely used.

Our fight on this day has fallen and failed.

I was ready for our young men to walk

in the blood and flesh of the enemy.

Now I am dissolving this death hunger

in my smith’s forge along with our armour.

My work here in forging steel and iron

to free every Irishman is over.

Our movement betrayed in perfidy.

Is the ghost of the Bruce here for us still?

We have had Cromwell’s blind atrocities

when we fell at Drogheda’s bloody siege.

Then James’s Boyne failure at King Billie’s hand

then with Vinegar Hill’s weeping widows.

All fought on the Fianna’s ancient fields

by the measure of lost generations

we Fenians would destroy foreign rule.

All for the bleached bones and broken pikes.

Death over death over death over death.

Long furrows sliced by pikes and bayonets

to bury the dead clan and lose these lands.

Yet here is the soil that blood has nourished.

Our long furrows plough-sliced for seeds to raise

new clans and fight for kingdoms of the air.

Not one village elder nor sweetest child

but young men from all the ages follow

to celebrate a good day’s victory

against the long wide measure of the earth.

Blood on the path garlanded with flowers.

But what is this pull of these ancient fields?

Green fields once fresh with red blood hot flowing

fleeing souls and tomorrow’s carrion.

Here swift butchery that a raining pike

Sliced wide both rider and his shrieking horse

in a motion of finely honed hatred.

Now someone’s broken and fragmented sons,

back and forth, back and forth in our long cause,

buried by the ages rolling seasons.

Sweet young boys damned in fighting old men’s wars.

Can I ask you all though why did you die?

I am a blacksmith, I can stand with you.

Were you fighting for your gods, your children,

or those ancient fields of the Fianna?

No — you were bribed by dark grey covenants.

Forever it has been for the nameless

to collect riches of empires you won.

Will our children know who really wins

when our gods demand blood, then leave the field?

Your early death in perpetuity?

*Referring to the Fenian Rising of 1867

The Father Will Now Answer Your Questions

“Is it a sin to kiss a Protestant?”

was the third anonymously written question

God’s chosen one read out in RE class at the end of term.

It followed “Why can’t Jews and Muslims

get into Heaven?” and “Can kissing a girl

make her pregnant?”

In that lesson words hung

on the hammer swing of a fading trust

pounding through muscle, sinew and bone

How much we could ever learn

from a middle-aged

and celibate priest.

We needed to understand,

in those airless moments,

if we were loved as Jacob was.

Though he wasn’t Esau,

none of us asked the unwritten question

“Where does our love of God draw its hatred from?”

A Sunday Night in Dublin 1962 in Rain After A Death

i.

Under a dark wet sky we came the long way

in rain and wind around the bay

so this emergent city would sparkle for us.

To see its main artery with the glistening figures

of Nelson and Parnell and its fabled claim

to width and significance, was our simple wish.

Passing the Pillar and the “Happy Ring House”

our grief would surely lift even for moments.

We’ll have the fizzing neon apparitions

of ‘Player’s Please’ and ‘Cafollas’ coffee bar

spatter the flickering glass and water-wet walls

with spectrum’s busy electric rainbows.

Thinking our thin beliefs might pull us through,

we were silent at all the proclaiming signs

of opportunity, promise and prosperity.

With our brother too soon departed all this dissolves

in the slow mist of old Dublin’s drizzle

and our sodden testimonies of denial.

ii

Male, single, twenty-two, St Kevin’s Ward —

you were leaving us slower than a feather fall.

Our truncated visits over long months, then

sudden as a door slam—gone.

Where are you, why have we stopped going?

I am eight and do not know how to be.

Without your temporal grip to hold

we have the unquiet devastation of a thickening hell

and your dreamed heaven diluted after this.

I know that isn’t you with the enveloping ghosts.

You left too young — you are beyond them still.

I am mute — I still want you to hold my hand.

Your mother calls for you screaming

“I shouldn’t have to bury my child” at us.

I saw that spat at our remnant family

in every smoke-filled room, though in every silent

church “Why is my boy undone?” whispered.

A mother’s child is forever, a mother’s child.

The People of Howth

I’ve watched you

and your swanky houses

on the coast facing south.

With the beautiful gardens

and the smooth wide roads

we never had.

Wide windows looking across

majestic Dublin Bay.

White carpets and white cats.

The manicured lawns and hedges.

The jumped-up accents

we never had.

On this pier

in this damp air

in my dyed army coat –

cut for these nights,

I look at the flash lives

we never had.

Think of me looking across,

dreaming of you lot.

Soft, moneyed and snuggy

with your grand central heating

and TVs and the holidays

we never had.

I’ll slide my way

across the bay

climbing the rugged cliffs

to crawl into your lives

with new found confidence

and empty bags of promise.

Leaving Ireland

Let’s take to the sea tonight and we’ll fish for diamonds on the sparkling horizon. Our dreams are way beyond the remnants of Dev’s ‘Dreary Eden’*. We’ll leave the old games behind shall we?

We grew up where the land meets the sea, where there’s rich and poor. One element fixed, one shifting, forever eyeing each other’s fortune. We’ll leave the old games behind shall we?

We have lived the numbing family privations and raw exposures to fate. Church and state feed on our hollowed out shells – such repugnant betrayals. We’ll leave the old games behind shall we?

Our hidden tattoos of pain, sorrow and loss are shaped like this place. Perhaps we can ink in some pleasure, joy and gains way over the sea, way over the sea. Leave the old games behind.

* – ‘De Valera’ (1939) – Sean O’Faolain

referencing Ireland’s emerging morally repressive society.