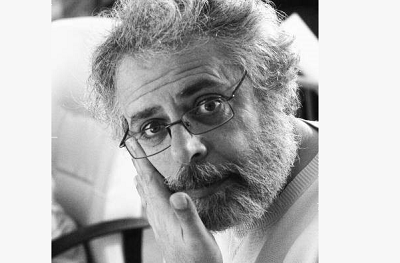

Jonathan Vidgop is a director, author and screenwriter. He is the founder of the Am haZikaron Institute for Science, Culture and Heritage of the Jewish People. He is the recipient of the Zeiti Yerushalaim Prize and the medal “For contribution to the development of the national spiritual heritage of the Jewish People.” He was born in Leningrad in 1955. In 1974, he was expelled from what is now called the Saint-Petersburg State University of Culture and Arts “for behaviour unworthy of the title of Soviet student”. Having worked as a locksmith, loader and White Sea sailor, he was drafted into the army and sent to serve in the Arctic Circle. Graduating from the Russian State Academy of Performing Arts in 1982, he was involved in 23 productions across the USSR, 12 of which were shut down. In 1989 he emigrated to Israel, where he has worked as a director, editor and researcher. Jonathan was awarded a special grant from the Israeli president for writing. Leading Russian publisher NLO published Vidgop’s latest book Testimony. Jonathan’s stories were published by the Los Angeles Review and the Pembroke Magazine, Nomads recently won 2022 Meridian’s Editors’ Prize in Prose. In 2025 Jonathan won a poetry competition conducted by Chinese University in Hong Kong. Vidgop’s works were published in more than 30 countries, he is the author of several books.

Jonathan Vidgop is a director, author and screenwriter. He is the founder of the Am haZikaron Institute for Science, Culture and Heritage of the Jewish People. He is the recipient of the Zeiti Yerushalaim Prize and the medal “For contribution to the development of the national spiritual heritage of the Jewish People.” He was born in Leningrad in 1955. In 1974, he was expelled from what is now called the Saint-Petersburg State University of Culture and Arts “for behaviour unworthy of the title of Soviet student”. Having worked as a locksmith, loader and White Sea sailor, he was drafted into the army and sent to serve in the Arctic Circle. Graduating from the Russian State Academy of Performing Arts in 1982, he was involved in 23 productions across the USSR, 12 of which were shut down. In 1989 he emigrated to Israel, where he has worked as a director, editor and researcher. Jonathan was awarded a special grant from the Israeli president for writing. Leading Russian publisher NLO published Vidgop’s latest book Testimony. Jonathan’s stories were published by the Los Angeles Review and the Pembroke Magazine, Nomads recently won 2022 Meridian’s Editors’ Prize in Prose. In 2025 Jonathan won a poetry competition conducted by Chinese University in Hong Kong. Vidgop’s works were published in more than 30 countries, he is the author of several books.

Nomads

By Jonathan Vidgop

For some time now I have been haunted by the intuition that nomads have settled in the North of the region where we reside. In this intuition I am not alone. We know nothing about them. We can only guess as to their rituals and customs. But our guesses tell us they are savage in their mores. We feel it, even though not one of us has ever seen them. In point of fact, we have only ever heard tell of them from one another. We do not even know for certain whether it is specifically in the North that they have settled. I should not venture to assert that they are not also to be found in the South. Nor is it inconceivable that they have taken refuge in the East and West.

This sense of looming threat beset us long ago. It is, after all, beyond argument that the nomads represent a threat to us. Back in our days of irresolution, some of us were struck by a serendipitous idea: looking on as our children erected little sand-towers, we resolved to erect a wall not unlike the one in China—a wall which would protect us, once and for all, against potential incursions by these dread nomads.

We have been building our wall for many years. No one could accuse us of being unindustrious. On the contrary, we are most of us diligent and conscientious. Nor is our region particularly extensive. And yet, all this notwithstanding, we cannot complete the wall’s construction. It has long been underway, but an end to it remains out of sight. The work in progress is robust, solid-stoned, a feat of architecture in and of itself. Many have poured their very souls into its construction, and observing holidays en famille at the wall’s foot has become traditional amongst us.

We take pride in our construction efforts. Our young couples—and, come to think of it, our oldsters also—often pitch up at the wall of an evening, there to while away an hour. Our pregnant women, too, promenade its length: as popular belief would have it, children born by the wall grow up to be bold of spirit. The wall has become symbolic of our valour; of that there can be no doubt.

Recently, however, we have come to remark that the construction of the wall has engrossed certain persons amongst us to such a degree that they have begun to forget about the nomads. Rumours are afoot that some are already asking whether it is, in fact, true that the nomads are closing in? Meanwhile, the most perspicacious of us have begun looking closely about them: we have, after all, never set eyes on the nomads and know nothing of their appearance. Could it be that they have already entered our city, adopted our dress and begun observing our holidays? Their aspect may even resemble ours. It has become a strange sight, therefore, to see a neighbour doggedly laying stones atop the wall—could it be that he too is a nomad?

And if the nomads are already amongst us, if they are giving birth to our children and erecting our wall, how many strong can they be? And in what do they differ from us?.. The fact remains that we are enemies! Then again, so much time has passed since we embarked on the wall’s construction that no one, I daresay, remembers how we were in prior days, before the nomads materialized in the North. What did we look like? And did we dress as we do now?.. We can no longer say with any certainty which of us is not a nomad. We can only regard each other with alert and searching eyes.

By force of inertia, construction of the wall continues; by force of habit, many still while away their hours at its foot. But we denizens of this region no longer observe our holidays with the joy and exultation of before. We all of us lead quiet, circumspect, fearful lives. Our children are not as carefree as once they were, the infants born to us grow ever fewer, and our old have begun to die early.

The dying, for their part, are often heard to utter these final deathbed words: “Could it be that I too am a nomad?..”