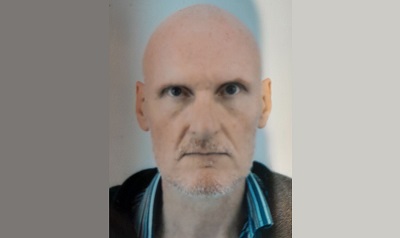

Simon Collery has been writing for over 25 years, exploring diverse forms such as web content, non-fiction, blogging, flash fiction, epistolary writing, short stories, and creative non-fiction. Particularly drawn to magical realism and moments of epiphany, Simon’s work often delves into themes of hope, joy, human rights, media, and life in developing countries. Their writing also reflects a deep interest in memoir, diary, and the creative process itself. Having lived on three continents, Simon draws inspiration from the richness of global experiences, people, and cultures. Writing primarily for personal fulfillment, they focus on discovering their own voice rather than emulating admired authors. Inspired by moments, places, and other artists, Simon’s work seeks to uncover the profound in the everyday.

Simon Collery has been writing for over 25 years, exploring diverse forms such as web content, non-fiction, blogging, flash fiction, epistolary writing, short stories, and creative non-fiction. Particularly drawn to magical realism and moments of epiphany, Simon’s work often delves into themes of hope, joy, human rights, media, and life in developing countries. Their writing also reflects a deep interest in memoir, diary, and the creative process itself. Having lived on three continents, Simon draws inspiration from the richness of global experiences, people, and cultures. Writing primarily for personal fulfillment, they focus on discovering their own voice rather than emulating admired authors. Inspired by moments, places, and other artists, Simon’s work seeks to uncover the profound in the everyday.

River Road, Nairobi – The Daily Grind

By Simon Collery

River Road was not on my itinerary when I first visited Nairobi, in 2002-3. The whole city centre was difficult to negotiate, with kids and adults trying to make a living. The Central Business District was a bit more organised than the older and less prestigious streets, but it was still scary. My only defence was to walk very quickly. If I wanted to cross the road, I’d do it where there were no traffic lights. When I saw a gap in the cars, which was generally when they had backed up almost bumper to bumper, I’d dart across before those waiting at the lights for slow movers would notice me. I didn’t spend much time in Nairobi, and I didn’t enjoy it.

When I returned in 2008 things were a lot different. People who had been trading or hustling in the CBD had been moved to less central areas, such as River Road, Lagos Road and Kariokor. I was able to explore some of the central streets at leisure and relax a bit. The private minibuses, called Matatus, and the motorbike taxis, called pikipikis, were no longer allowed to operate in the CBD and the traffic was light outside of peak times. It didn’t seem like such a bad city now. There were cheap places to eat even in the centre, and several large coffee shops. It didn’t take long to find my around and I became curious about the some of the other areas. I decided to start with River Road and the areas that the matatus, pikipikis and buses were compelled to use.

These streets were warrens of activity, with traders, legit and less legit, operating on the edges of the footpaths, against the walls, in doorways, between pillars and anywhere you could find a small space without blocking the narrow path that ran between the folded sacking, tarpaulin, cardboard and plastic covered areas that traders would use to mark the boundaries of their pitch. There were small gaps at entrances to shops, with traders on the steps of some. There were even traders who walked around, carrying some of their goods on their heads, the rest stowed elsewhere. The peripatetic partner. It was hard to believe that any of them could make money, given the competition. There seemed to be more traders than customers on this endless chessboard.

The goods for sale were mostly the usual, with a lot of agricultural supplies, such as seed, pesticides, implements, parts for tractors, livestock feed and the like. There was food and drink, clothing, accessories, anything you’d find in a market. It might have been my imagination, but it felt like there were a lot of rubber-stamp vendors. Every NGO and community-based organisation, and there were many, needed a rubber-stamp. So did every business, from the trader selling goods straight from the farm to the big stores and supermarkets. A rubber-stamp had no legal standing, but they were used on receipts and other paperwork. They were used by officials and, as an immigration officer said to us one time we were crossing the border between Uganda and Kenya, ‘Without a rubber-stamp, I can do nothing’. Even solicitors used them, and the rubber stamp may have been the closest they ever got to the law.

There were Bruegel-style beggars, displaying signs of leprosy, polio, broken bones that had knitted up crooked, elephantiasis, Buruli ulcers, horrendous burns and missing limbs. One man, who I thought had a child’s head resting on his lap, turned out to have scrotal lymphedema. Some NGOs would provide people with prosthetic limbs, wheelchairs and other devices. But recipients would often sell them because their obvious impairment was the only thing available to give them credibility as beggars. And, like the hawkers and traders, competition was high.

The atmosphere on River Road was strangely attractive, thrilling. I returned a few times despite knowing that it could be risky for a foreigner. However, I had to pass through these roads on the way to the out of town and city to city minibuses and coaches. One day, going to the coach office to get a ticket to travel to the west of the country, which would take a whole day, I took a detour through River Road. First, it was just the usual pulsating hive. But suddenly I heard shouting and saw hordes of traders with their wares balanced on their heads, some dropping things as they went, running and shouting as if they were in mortal danger. In a way, they were. The city askari had arrived.

These enforcement officers are after any traders and hawkers who do not have a licence, or who are illegally using a part of a public walkway. They don’t carry guns, luckily, but they carry whips, sticks and anything else they can mete out punishment with. They will attack anyone, male or female, especially young, old, disabled or just slow people. They don’t discriminate. They’ll hit out in every direction, and they’ll shake down anyone they catch. If they pick up people who have no money, they’ll take them to the police cell and offer them the option to call someone to bring money to get them released. They’ll continue to beat people in the cells, but apparently, they eventually let them go if no one turns up to pay their ‘fines’.

There’s no need to ask who has a license and who does not. Unlicensed traders occupy non-approved areas and must be ready to pack up and run as soon as word goes around about the askari. I couldn’t run on River Road, even without the unofficial marathon that I ended up in the middle of. I concentrated on keeping my balance, difficult when most of the heavy loads on people’s heads are about level with mine. It wasn’t far from one of the main roads on the outer edges of the CBD, where the racing traders would have to quickly blend in with ordinary shoppers and pedestrians.

The askari didn’t follow them into the CBD. Perhaps it was outside their jurisdiction. I was surrounded by traders, breathing heavily after the exertion, and I expected them to be as panicked as I was. But they were laughing and joking, as if this was a game. They must have been relieved not to be caught and shaken down. They looked like parents taking part in a bizarre version of school children’s annual egg and spoon race. The city askari had to wait for another opportunity. They wouldn’t have to wait long, as the traders quickly returned to their squares.