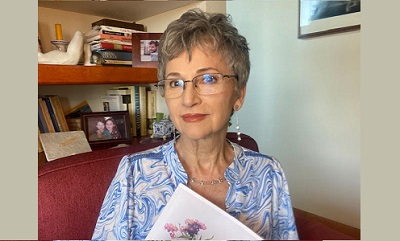

Alicia Viguer–Espert, a three times Pushcart Award nominee, was born and raised in Valencia, Spain. Her work has been published nationally and internationally in journals, print media and anthologies. Winner of the San Gabriel Valley Poetry Festival on 2017, she is also the author of three chapbooks. In addition, she’s included in “Top 39 LA poets,” “Ten Poets to Watch 2018” and “Bards of Southern California: Top 30 Poets,” by Spectrum.

Alicia Viguer–Espert, a three times Pushcart Award nominee, was born and raised in Valencia, Spain. Her work has been published nationally and internationally in journals, print media and anthologies. Winner of the San Gabriel Valley Poetry Festival on 2017, she is also the author of three chapbooks. In addition, she’s included in “Top 39 LA poets,” “Ten Poets to Watch 2018” and “Bards of Southern California: Top 30 Poets,” by Spectrum.

She Lifts Her Burka

I wonder how tough this young Kabul woman has it. This woman who shows me her lovely fifteen years old face, polished nails bright red, and the green eyes of a 1985 National Geographic cover. A youth already betrothed to a man three times her age, a friend of her father’s, luckily with only one wife, she whispers. Leaning on the noise of a building’s façade to hide her dismay, or protect herself from viewers, she pushes her chaperone’s hands as they try to pull the burka back. At home family prepares Halwa and praises God for the engagement. Nervous, asks about life in Europe, if I am allowed to dance until sunrise, how often women die in childbirth, whether I am married, and if my husband beats me. With the last question her smile disappears. I survey the snowy ridges circling us like rapacious birds starving for prey in that frigid December morning. He’s a good man, maybe he’ll let me go back to school, she says frowning.

I think about her often, her beauty, youth, pray fate will treat her with enough benevolence to raise healthy, educated children. She wouldn’t have had a chance, untrained as she was, but her daughters did before the Taliban. Now icy clouds of misery engulf the city, women sit around clanky kerosene stoves without kerosene, debate the dangers of defying the jailers to have a life of their own, or else.

a bright light

fades fast

under the burka

Previously Published at Live Encounters

Remembering the Monastery

Between the damaged roof and the walnut tree

slightly to the right, I watched Venus appear

using a celestial method long discovered

by astronomers who registered astral details

as we, scribes, illuminated manuscripts

in the dim light of the scriptorium.

Those days were sacred, when a robin

sitting on the window sill to preen its tail

caught the brothers’ attention and they

lifted their heads from smooth parchment,

interrupted grinding lapis for a minute

to smile at birds’ ease to reach heaven.

Today the empty monastery stands silent,

stone walls crumbled, beehives destroyed,

all bees dying in clusters from pesticides,

its orchard burned years ago, the pigsty

covered with ivy, only a single walnut tree

stands by the wooden door cracked by sun,

which, like me, was once new and strong.

In those clear mornings nothing was futile,

the bundles we carried were not burdens

but a fair exchange for the gifts received,

silence, blue skies, tolling bells falling

like rain in May when it was most needed.

The roads leading to that door were infinite

and no wind blowing over the hills stopped

a pilgrim seeking the solace of an inner

contact with Andromeda, Cassiopeia, or

their own soul, from getting their reward.

In another life, eons ago, I must have been

one of those monks waiting for the Beloved,

leaning on the walnut tree, closed eyes focused

on the heart chakra counting each breath,

which like heartbeats, connected to my soul.

I remember an eagle resting on that same tree

tried to tell me a secret, but I didn’t listen.

Previously Published at Altadena Poetry Review

Thirst and Fire

Flames crepitate too close to your home,

heat scorches trees desiccated for lack of water,

but still standing straight like Olympian torches.

Here in the Parque Natural de Moncayo,

pine trees used to lean on each other with confidence.

Now, the sound of snapping undergrowth scares them.

Bright, lustrous greens, dull already, turn red

before bursting into the fireworks of superheated forest fires.

You want to take the boat, now smoked charcoal,

down to the river, but the river hasn’t been in its bed

for a very long time, after pesticides

exiled trout, frogs, and salamanders

to some undisclosed abandoned fishery.

You believe dry seeds and spores will sprout

when rains return, temperatures will cool,

overgrazing at the valley will stop,

and legislation will forbid slaughtering cattle

on the altar of profitability, but you doubt it.

You wake up unsure of whether what you see

is fog, shadows, or smoke from perennial fires

striking the flora and fauna of your mountains.

You pray to Tlaloc, a god from another continent,

because your gods, already consumed

by thirst and fire, have no chance of resurrection.

Previously Published at Sin Cesar

Sand

Confronted with a sea of bleak monotone beige, I thought about my childhood golden dunes of El Saler Beach covered with Pancratium Maritimus’ blooms overlooking the sea’s impossible shades of turquoise. Here colors were excised.

How the bus driver stayed on the road was a mystery since it often appeared hidden by sand. I couldn’t understand why he stopped, but then a man stepped on the metal rungs, nodded, and without a word sat down on the floor since there were no empty seats. Through the glassless windows I searched for a hamlet, a caravan, a truck, a donkey, anything that could have brought the man to this non-existing bus stop on the desert. Nobody seemed surprised or even curious. The bus maintained its course south to Kandahar, Herat long gone.

The new traveler’s complexion of almond shells reminded me of Jesus, with his dark moustache below calm warm eyes. I considered whether the Christian Rabbi had worn a turban, but when I saw the man wiping fine sand dust off his face with the turban’s tail, I decided that yes, he must have needed one. Nothing happened for an hour until the traveler without a seat leaned his head and arm on the lap of the man next to him, and closed his eyes. To my amazement, they never spoke, never made eye contact, both pretended that the fact that one man took another’s body part as pillow for his comfort, never happened, or more likely I witness something beyond my Western comprehension.

I thought of Jesus again following the same Silk Road as Alexander, crossing the treacherous Khyber Pass in his way to India saying: “the son of man has no place to lay his head…” But someone without lifting his arms to stop the bus, without paying the fare, or talking to anyone, found a place to lay his head.

dusk desert sand

a man leans on

the lap of Infinite

Previously Published at Panoply