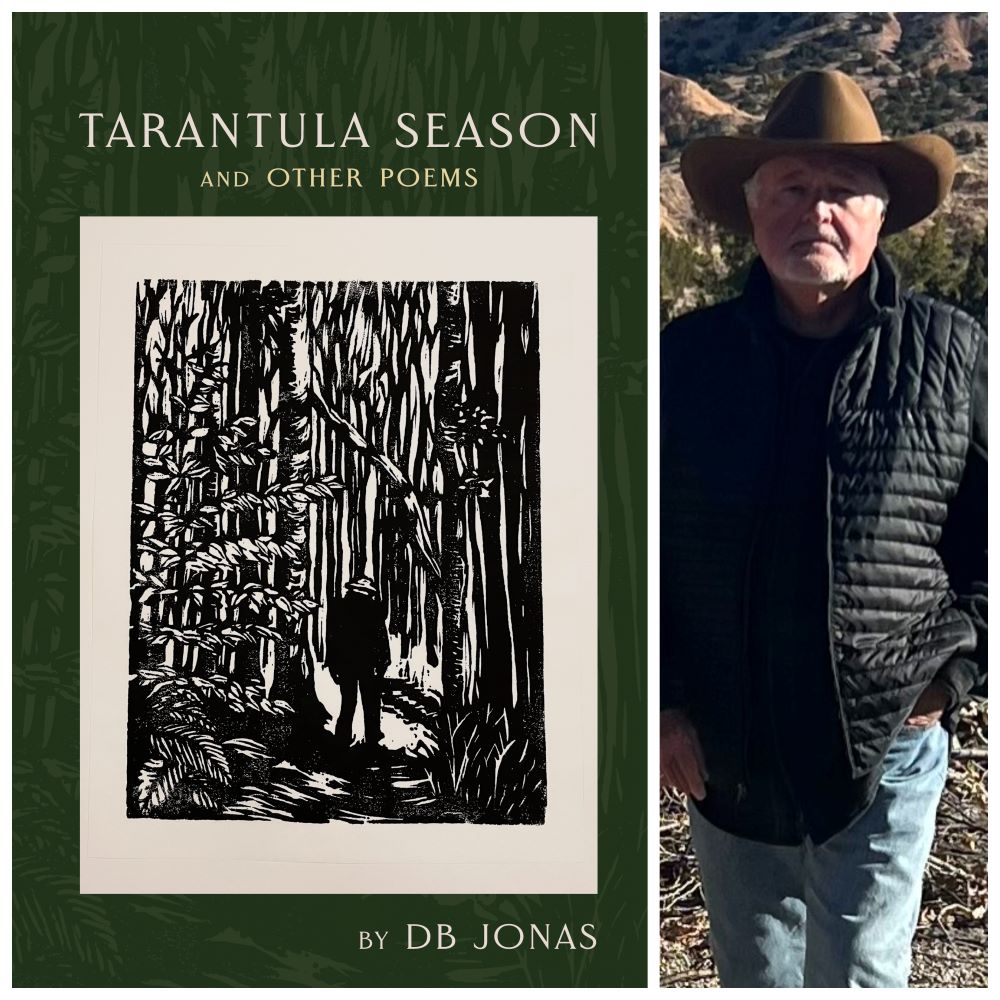

Tarantula Season by DB Jonas

A Review by Matt Mooney

Our Velocity is the title of the introductory poem in Tarantula Season and Other Poems, a first collection by the New Mexico poet DB Jonas. In this opening piece, we find ourselves in motion at high speed straight away, moving through time, heading in the direction of some uncertain mark, possibly in the direction of origin itself, the centre of space-time, into the precincts of The Big Bang. Yet, as this poem’s first lines tell us, we are unaware of such cosmic velocity, the speed of our lives, the breeze it ought to make, for “You cannot see it moving / over the slick-rock face,…// You cannot feel it lift / the nape-hairs of your dream”. And try as we may, we cannot manage to grasp this velocity and its source:

‘yet we

can only just approach

that always vanishing place

across a fast-diminishing,

a never-quite-closing,

distance’.

From this point forward in this lengthy tome of supercharged poems comprising both incisive thought and learning, we can only glean the insights we crave in poetry by boldly entering into Mr. Jonas’ excavations into the human psyche, armed as he is with an array of analytical instruments and perceptions trained on our everyday existence and informed by a vast array of philosophers, painters, and poets whose inspiration he’s gleaned from a diversity of cultures and languages. Such is the apparent background to the richness of material and intellectual expertise of this master writer who is DB Jonas. We, his readers, are so much the richer for it. We the students at his mobile university. We the poets who marvel at his craftsmanship.

Throughout this collection, we go panning for gold dust and find it hic et ubique. He has endowed us with a university of thought, its doors wide open to the wise.

Having said this, I will try to lead you through the corridors of his mind and those whose precincts he has himself chosen to enter. While defying easy assignment to any specific subgenre of poetry, this collection flirts with many genres (ekphrastics, character poetry, narrative and meditative lyrics), prominent among which is what we’d call “nature poetry.” What has filled me with wonder, apart from his insights into the mind of man, is his ability to bring wildlife, at times strange and exotic, alive in his poems. Even the so called domesticated Catullus the cat has his role to play in a poem called Beauty’s Beast, a poem that brings out the best in DB, as we are invited to observe:

‘the quickened pulse

of the spellbound predator,

as burning sunlight

and unseen shadow startle

wild dilations in the eye

of his luminous

mesmerizing prey.’

Or in the case of the red-tailed hawk, we’re invited to listen as:

‘Out past the tangled streams

and raven-harassed heights and all

the gaudy constellations

of my own pedestrian thought

the lingering savage pitch

of an anxious distance in the sky

and barely seemed to see

against the sunstruck blue

her faint dihedral spiraling

through the mututinal light

at the far limit of the visible’

One could compose a handbook on all the birds, both fierce and timid, that fly in and out through these poems, and the other animals too, both great and small, by land and sea, that inhabit his “material world”, his kingdom on earth – the Real, in his own words, into which he finds passage, an escape into the arms, however cruel and indifferent, of Mother Nature. His turkey vulture in the poem Lords of Our Air is a case in point:

‘Your lazy shadow’s stealthy transit never fails

to spark an apoplectic outrage in these dogs of mine.

They sense dark meanings in that brazen span of yours,

your scornful hovering approach, your eloquent disdain’.

He almost humanizes the great horned owl (in the guise of the god Hermes), and no painter could do as well as this:

‘When we pass along the mumbling ditch the winged helmet swivels, a languid lid

shuttering awake awakens the landscape whole, imploding into her mercuric stare.’

Maybe, in the following powerful lines from This Material World, A Benediction, a clearer picture emerges of how the poet enters into the world’s body and soul and finds the infinite in a startling fashion:

‘Out in this air a wildness cries out only to itself, lives only

once to hear its whispered voice alive among the swaying trees’.

This leads on to some of the finest lines in the book, the closing lines of the poem, and brings us closer to an understanding of the poet’s innermost thoughts on his own place in the scheme of things. The magnificence of his language and imagery reflects the vastness and depth of the silent universe broken only by the joyful sound of ‘a thousand cranes’:

‘from here, from somewhere past seeing,

you can hear the wild clamor

of your interrupted solitude.

Listen as, within your precious

silence, above the pearly dawn,

a thousand cranes in weary squadrons

make joyful noise’.

In the manifest craft of this poetry, as shown above, the poet gives the impression that every shoe fits the foot just so; no need of shoo-ins. Words knit into words, creating picture after picture, like a reel of film rolling, narrow enough on the page to keep your eye moving through the precision of each poem’s specific shape, sized carefully into meaning. In one particular poem, What Returns, about loss, he cleverly knits a full page poem into one long unpunctuated sentence in a mind-boggling tour de force.

In The Dreamer he captures the essence of fierceness and wildness dormant in a domestic dog, observed by his human “masters” in the midst of his dream, who wonder:

‘What perfumed prodigies

of the canine dream

have filled the thirsty nostrils

of sleep, provoked

the eager quiver of your limbs

thrashing here beside us

in the noonday air,

the sinews of your howling

blood-lust lost

in joyous hot pursuit,

your innocence abandoned

to the chase, your savage beauty

recovered, resplendent.

in full cry?

As in Beauty’s Beast, the domestic cohabits with unfettered wildness in these pets. I suppose it begs the question: What does this all say about us?

In the poem Wolverine we see how sad and awful it is to witness the withering state of one among the wildest in the animal kingdom when trapped and caged:

The keepers said they saw her shining coat grow dun

and darkling eye grow dim beneath their probings

and inspections on that lengthy day of first captivity

as she lay spent and etherized upon her mat, her dusky

fires fading in the sinkhole-weeks that followed’.

The titles of all these poems, their headnotes, his literary, artistic or philosophical references, and the way these markers materialize as significances in the body of his poems, lead one inexorably into research and further study out of sheer interest and the curiosity he has aroused in us.

From this point of view the whole book has such a solid base of gleanings from the “greats” who have inspired many of his scintillating albeit sometimes abstract poems, that I have begun to understand this book as a seat of learning, a veritable literary resource library, for all his readers, whose strongest poetry leaps out at us from its pages.

Leaving aside all of that, skirting around poems heavy with his meditations, there is even more to savour here from works composed in a lighter and more personal vein, where he himself declares his hand. His private life is elusive enough in Tarantula Season, or at least hard to find behind his perambulations on existence and meaning, in which he engages us and intrigues us as fellow creatures. I think he sits us down and tells us the real story in Salem Vigil. If we go by the meaning of Salem, ‘Peaceful, safe, complete, perfect’, alongside its reference to the Massachusetts town that was home to the notorious witchcraft hysteria of the XVIIth century, the picture may get clearer on DB Jonas;

‘The loss of my last living child

drove me long ago

from my neighbours’ company

into this tiny hunter’s cabin

out past the smokehouses

among the whispering elms,

with squirrels and voles and owls

my only companionship,

and the little family of foxes

that eat from my hand’.

I have found that poem, marked for me by the last three lines in the above, to be most appealing and memorable, ranking with some of his best in the book.

The poem Darkly does a lot for me as well. Its simple language and its musical flow, combined with stunning imagery, its sayings on the signs for bad weather at sea, all add up to remind me of an old poem, Rosabelle, by Sir Walter Scott.

‘As dawn breaks hard along the ashen ridge

As mare’s tails sweep across the scarlet swells

we seem to hear behind the rumbling hills

our granite mountains on the move again’.

He goes to Galileo for the title and tone of Eppur, si Muove, (‘But behold, it moves’).

These are profound lines from the poem and they go a long way in discovering the real mindset of the poet on the subject of creation and our existence:

‘So faintly hear creations roaring fire

in the ancient melodies of man’s desire.

And most still thought

they could detect the lingering odours of divinity,

a greasy scent of punkwood cloying in the air,

though all at once, in the absence of the dancing master,

we all could only seem to choose to join the dance,

surrendering the future of our complicated past

to chance because, behold, it works! the vast

indifference of it all…’

Here I seem to be about to rest my case and say that it strikes me as I ruminate on the contents of this book of poems that birds and animals surge towards us in our understanding of the mystery of life, whereas in the case of Homo Sapiens we get all tied up in a maze of suppositions.

Quite frequently, these poems present us with an ars poetica. On the artful poet in the poem Perverse Practice he finishes with a stanza which resounds with truth for us:

‘So if poetry unleashes something

harboured in the words, perhaps

it’s not a matter of some latent

power there or vivid insight which

an efficacious eloquence supplies,

but an urgency no speech can silence,

an entreaty to which every verse replies’.

Along the way in his poems he hits us with some dramatic descriptions of his natural surroundings. In his case he looked upon them as his own where he felt at home. These lines are from his Stopping in the Mountains:

‘Shortly, the deafening roar of canyon cataracts

faded as I climbed, silenced in piney stillness.

The steepening path delivered me into cloud’.

I can’t but refer to the poem T’ao Ch’ien to Hsieh Ling-Yun that held me to ransom for a long time, so engrossing was its philosophy and the poetic style in which it was written. In it he holds a mirror up to poets, urging us to look at ourselves again and the craft we practice:

‘For the immortal verses

we intone in the moonlight

are never monuments to immortality,

don’t you see, but an eternal music of loss,

of transience, of defeat, of careers abandoned

and love unrequited, the precious melodies

of mortality itself, fashioned by time, to insist

in the memory of your unborn reader,

and perhaps to be shared one day’.

In The Lens Grinder, a poem about Baruch Spinoza, he says:

‘I think on how my real business lies

in instruments of curious transparency,

of magnification and slow time,

designed to bring the world up close,

to arrest for the briefest instant the restless eye’.

Rothko Chapel is an extraordinary poem of some length, which explores the effects of visiting the famous collection of Marc Rothko’s work in Houston, Texas, and the problematic experience of encountering a body of work, and the space which presumably “contains” it, as a challenge to our concepts of interiority, our confident self-containment as detached observers, where:

‘the space, whose intimate capacity,

just like your own, seems vaster by a mile

than the world itself’.

And if the Rothko poem presents us with a paradox of identity as isolation, the poem titled Odradek, a curious image taken from Franz Kafka’s Cares of a Family Man, appropriates this fantastical object as a metaphor for the curious ineffectuality, the fundamental uselessness, of art, and of poetry in particular, which arises not from capability, in this poet’s world, but from an inability not to exist, a radical passivity in things, “an unconquerable fatigue”:

‘…advancing, advancing across an endless terrain,

gaining indiscernible progress toward some distant,

shining purpose, an urgent purpose long forgotten’.

Retracing my steps somewhat, I would like to quote from a poem that stood out for me, Aminadav to Avigdor, It’s hard to single out any favourite in this large tome of such high literary quality. Its poems both charm and challenge you in different ways in their explorations of the human psyche, the perplexity of living, our relationship with nature, and the notion of infinity.

This particular poem has a tickling touch of humour in its own existential way. The headnote says it is about “The Philosopher in Search of an Audience”. It’s very much like a scene from a play, something we might find in Beckett. Avigdor is encountered along the road by the chatty “philosopher” Aminadav carrying a large rack of cooking utensils for sale to households. Aminadav, overtaking him, says:

‘I’d hoped you wouldn’t mind a little company today

my friend, along this empty stretch of road.

I was humming to myself back there, as ever,

when I spied you up ahead , or truth be told,

when the jangling of your strange festoonings

reached my ear, and I picked up the pace …….’

He’s met with silence, so the philosopher moves on and makes some remarks about Avigdor which led to him saying in the finish, taking his silence as validation, that he would listen back to him:

‘as I hurry on ahead for the happy disappearing tune

that copper, bronze and iron make, your armillary’s

arbitrary euphonies, whose ringing notes collide

like starlight in the mind, brighter than speech, clearer

than thought, the insensate sound of jingling matter

set to rocking with your stride’.

Leaving it at that, I will finish my meanderings through this minefield of intriguing and delightful poems, some of which can best be fully enjoyed at the price of fully understanding the philosophical and literary references embedded in the titles and called up by their many inspirations. I, for one, feel greatly enriched on the Who’s Who of our literary heritage after many readings of this incredibly brilliant contribution to English literature, and know that I’ll be renewing my acquaintance with it for a top up from time to time.

Tarantula Season and Other Poems, a book title significantly reflecting his love of the natural world, has made its mark for me. This poet from New Mexico is a music lover, as evidenced in his rare autobiographical poem Whistling in the Stair, and long will I seem to hear the echo of that poem’s teenager whistling, ‘in a resonant stairwell that no one ever used.’ That was his paradise. Then he turned to poetry. Here he has at last found his audience.

Matt Mooney is a native of Galway and lives in Listowel, Ireland. He has five collections of poetry in English, Droving (Self published, 2003), Falling Apples (Original Writing, 2010), Earth to Earth (Galway Academic Press, 2015), The Singing Woods (Galway Academic Press, 2017), Steering by the Stars (Revival Press, 2021) one in Irish, Éalú (Coiscéim, 2021). He won third prize in the Irish language poetry competition at Ballybunion Arts Festival 2022 and he won the Pádraig Liath Ó’Conchubhair Award in 2018. Matt runs the Cúirt Filíochta at Listowel Writers Week each year and is a deputy editor and poetry reviewer for The Galway Review. He has been long listed for the Fish Poetry Prize and The Francis Browne Poetry Competition. He has been a featured reader with Ó Bhéal in Cork and On the Nail in Limerick, West Cork Literary Festival and Féile Raiftearaí.He has also featured on Lime Square Poets and Cultivating Voices Live Poetry. Matt’s work has been published in Howl, The Stony Thursday Poetry Book, The Blue Nib, Feasta, The Mill Valley Literary Review, Vox Galvia and Live Encounters, among others. He has a number of multilingual publication credits as well, including The Amaravati Poetic Prism, I Can’t Breathe, Immagines & Poesia, Canto Planetaria, and Ukraine, an Anthology of War Poems.

Matt Mooney is a native of Galway and lives in Listowel, Ireland. He has five collections of poetry in English, Droving (Self published, 2003), Falling Apples (Original Writing, 2010), Earth to Earth (Galway Academic Press, 2015), The Singing Woods (Galway Academic Press, 2017), Steering by the Stars (Revival Press, 2021) one in Irish, Éalú (Coiscéim, 2021). He won third prize in the Irish language poetry competition at Ballybunion Arts Festival 2022 and he won the Pádraig Liath Ó’Conchubhair Award in 2018. Matt runs the Cúirt Filíochta at Listowel Writers Week each year and is a deputy editor and poetry reviewer for The Galway Review. He has been long listed for the Fish Poetry Prize and The Francis Browne Poetry Competition. He has been a featured reader with Ó Bhéal in Cork and On the Nail in Limerick, West Cork Literary Festival and Féile Raiftearaí.He has also featured on Lime Square Poets and Cultivating Voices Live Poetry. Matt’s work has been published in Howl, The Stony Thursday Poetry Book, The Blue Nib, Feasta, The Mill Valley Literary Review, Vox Galvia and Live Encounters, among others. He has a number of multilingual publication credits as well, including The Amaravati Poetic Prism, I Can’t Breathe, Immagines & Poesia, Canto Planetaria, and Ukraine, an Anthology of War Poems.

http://www.mattmooneypoetry.com