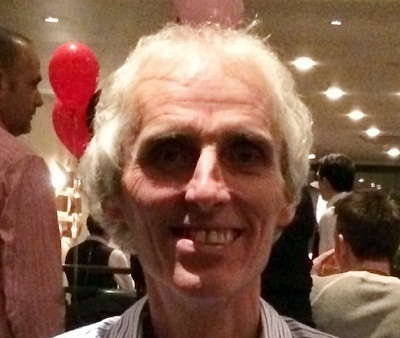

Chris Morey was born at Cowes, Isle of Wight, England and educated at University College London. He has done a wide range of jobs – many in the IT industry – and community projects. He’s widely-travelled, and enjoys performance art and reading. He has been writing creatively since 2015. He currently lives and writes in Marsaskala, Malta. Several of his stories have appeared in curated literary magazines.

Chris Morey was born at Cowes, Isle of Wight, England and educated at University College London. He has done a wide range of jobs – many in the IT industry – and community projects. He’s widely-travelled, and enjoys performance art and reading. He has been writing creatively since 2015. He currently lives and writes in Marsaskala, Malta. Several of his stories have appeared in curated literary magazines.

Eve

By Chris Morey

“Manfred, pay attention. What’s that word?” Eve pointed at the page.

Manfred kicked his heels against the bench. “Dunno.”

“Let’s work it out, then. Look – ‘ult’ – ‘im’…”

“Don’t care. This is boring.”

Eve found it hard to disagree. But at least a smattering of Latin was essential for any ambitious young man of noble family. That was why a poor girl, effectively if haphazardly educated by a broadminded village priest, found her learning of service to Manfred’s parents.

“Alright, maybe that’s enough for today. Would you like me to recite some poetry? Or shall I tell you more about Prince Florizel?”

Manfred perked up. “Florizel, please, Eve!”

“Well, when Florizel came over the crest of the hill, he saw a puff of smoke rise from behind a big rock. He knew it was –”

‘A dragon!” Manfred shouted.

“That’s right. Now, what did he do?”

“He drew his trusty sword, and –”

Rodolf, the seneschal, burst in without knocking. “Manfred, you are to wash and change before the midday meal. Eve, you are to wait on Lady Gertrude, immediately.” He flapped his pudgy hands. “Quick, now!”

Eve made a vulgar gesture to Rodolf’s retreating back, and shooed Manfred before her down the draughty corridor.

The Lady of the Manor sat stately in her parlour, her considerable bulk overflowing her upholstered chair. “Ah, Eve. I wish to advise you of a change of arrangements. Manfred tells us he no longer wishes you to be his tutor. In his own words, ‘it’s a waste of time’.”

“B-but…” Eve stammered, then found her voice. “Manfred has never said any such thing to me. We often talk of his future. With my tutoring, he could well enter the university, then win a place at court. He might rise to be a trusted counsellor of the king, reflecting honour on the family, and –”

“I know nothing of that,” Lady Gertrude interrupted. “He wishes to be taught the manly arts, and he will be placed under an instructor skilled in arms. You are therefore relieved of your duties, and may return to your village.”

Shock stilled Eve’s tongue. She had tried her best to make learning pleasant for Manfred, had seemingly gained his confidence and even affection, and made him as apt a pupil as a ten-year-old boy could reasonably be. But behind his compliant mask, he’d gone behind her back and tattled to his mother, demanding to be a boorish, sweaty warrior, ignorant of all the finer things of life. Tradition might urge a martial career on an only son, but that for tradition!

“Besides,” Lady Gertrude went on, “it is unfitting for a boy of noble stock to spend his time among women and girls. And even less fitting that a young woman such as you be thrown into close association with my brother-in-law.”

Eve shuddered with revulsion. Armin had often forced himself upon her after his drunken carouses, odours of sweat and stale wine nauseating her as his gross body pressed her down on her pallet. A few thrusts always sufficed him, which was the only positive aspect of the whole disgusting business.

“Nevertheless, you have served well. Take these ten ducats for your pains. They will augment your dowry.” Lady Gertrude proffered a leather purse. “You may go,” she added, inclining her head toward the door.

Trembling with fear and anger, Eve retreated. Her reward for two years’ labour a miserable ten ducats! Farmhands were better paid. Gone were her hopes of a civilized existence, of gaining a suitable marriage portion, of meeting a soulmate of similar tastes. Her best prospect now would be a carter or miller, a more likely one a day-labourer. A smoky, mud-floored hut shared with the domestic livestock, an ever-growing tribe of unwashed children, lice, scurvy, early degeneration and death – if a plague didn’t carry her off first.

Unless Robert from her ancestral village would… She’d admired him since her early youth, and on the rare occasions when they met, his looks and words might have hinted at a reciprocal interest. But Robert’s family was a prosperous one, and his father would look askance at a dowerless bride for his younger son. Best to push vain imaginings aside.

What to do, to salvage her shattered dreams? Her first impulse, to throw herself on her bed and weep tears of frustration, would avail her nothing. Should she slink away without repining? Father Aloysius, who had taught her her letters, preached a creed of submission and abnegation. But Olenia the Healer, whose searching gaze even the village hetman feared, boldly mocked his doctrines. “His ‘God’ allowed himself to be put to death by mortals!” she spat. “Milk and water! Imagine the old gods being so supine!”

Olenia was right. Eve’s shock and confusion coagulated into cold rage. Cast aside like a worn-out shoe or shift, betrayed by a spoiled brat who’d scorned her priceless gift of learning! True gods would take due revenge, using her as their instrument.

She turned her steps toward the kitchens, peaceful after the bustle of preparing the noon meal. Three kitchenmaids, all known to her, stood chattering.

Eve opened without ceremony. “This is the last time you’ll see me here. The old hag’s turned me off.”

Marta and Emilia chorused, “No!” Emilia added, “If you ask me, you’re well out of it.” Only Beatrix showed genuine sympathy, embracing her. “Eve, I’m sorry.”

At the kindness, Eve’s tears began to flow. Beatrix drew her aside. “Come into the pantry. It’s quieter there.”

Among the jars and bottles, amid savoury and spicy scents, Eve told her tale, punctuated with Beatrix’s interjections of shock and disgust. As she recounted events, her anger rekindled. But how to carry out her resolve?

A trencher caught her eye. “What enormous apples! And so red – like fire, or blood. Not like those sour green things from our trees.” The tumblers of her mind clicked over, formulating plans. No one could resist such a delectable offering. No one…

Beatrix’s voice brought her back to the present. “Sweet and juicy, too. They come from the south, beyond the mountains. They cost the earth.”

“Can I…?”

“Take one? I suppose it won’t be missed. Only one, mind.”

“Bea, can I ask a big favour of you? A last one.”

“As long as it’s something I can do.”

“I’ve learned of a new love-philtre, and I need liquid honey. I’ll give you some to try on Simon.”

Beatrix’s eyes lit up. “Certainly.”

While Beatrix busied herself with a ladle at a large crock, she regaled Eve with another instalment of the Simon saga. “I’m sure he’s starting to notice me. Do you think he’d like me better with my hair up, or down?”

Eve finally made her escape, her next stop the apothecary’s workroom.

Basil snored in his chair, his remedies powerless against the onslaughts of extreme old age. Shelves of jars filled a whole wall. Ignoring the leer of the stuffed baby crocodile suspended from the ceiling, Eve scanned the crabbed script of the labels, looking for ‘Poison’. What a blessing she could read Latin!

There. She took down and cautiously unstoppered the jar, drew a waft toward her with the flat of her palm, as she’d seen Basil do.

An acrid, almondy odour: useless for her purpose. Quickly, she replaced the stopper.

On the shelf below, white crystals, odourless and hopefully flavourless, seemed a better prospect. With a spatula, she scooped some into a small vial. Basil slumbered on.

When she emerged, the meal was over. Belching men-at-arms jostled each other in the corridor, cackling with laughter at an obscene joke. Evading their attempts to fondle her breasts, Eve gained the sanctuary of the maidservants’ bedchamber, deserted at this time of day.

Pausing only to let her racing heart subside, she made her preparations. Fifteen minutes later, she set out for Manfred’s room, covered platter in hand.

Manfred greeted her with surprise. “Are you still here? Mama told me she’d sent you away.”

“I’m going soon, Manfred. I’ll miss you.” Liar. “But I’ve brought you a parting present – honeyed apples.”

“Ooh!” Manfred stretched out his hand.

“Gently, now. Look at the colour of the skin, red as rubies.”

“What are rubies?”

“They’re gemstones. Very rare and valuable, like these apples.”

Manfred needed no further persuasion, the slices disappearing like magic.

“They’re much nicer than the ones from the manor orchard. Where did they come from?”

Eve drew a deep breath. “From a special tree, deep in the forest. Are you ready for an adventure? A real man’s one?”

Manfred leapt to his feet. “Oh, yes!”

“Let’s go and find it.”

The manor’s well-fed inhabitants dozed or slept. They crossed the courtyard unnoticed, disappeared into the surrounding shrubs and gained the forest edge. Inside, Eve headed north toward the thickest part, impassable on horseback and thus unsuitable for hunting. No one from the manor came here, perhaps no human creature at all.

Manfred lagged behind. “My stomach feels funny.”

“Because you ate those apples too fast. It’ll pass.” She led him on.

Under a spreading oak, Manfred sank down. “I can’t walk any further. I feel faint.” He grimaced.

“Rest there for a moment, then.” Eve turned her back, drizzled honey onto the spatula, sprinkled on crystals, held it to his lips. “Try this, it’ll help.”

Manfred licked at the honey.

“All gone? Good boy.”

#

Manfred lay cold and still. Eve steeled herself to rifle the body. A gold neck-chain, a ring with a red stone – carnelian or garnet –a pouch containing a few gold coins, vanity for a boy who needed to buy nothing. She scraped up dead leaves and roughly buried the small corpse. Then, time to be away.

#

She knew the direction of her village, and how to navigate dense woods by the growth of moss around the base of trees. Occasional glimpses of the sun confirmed she was traveling aright. As she walked, unwelcome thoughts arose: she was a callous murderess, whose revenge overtopped by far the offense against her. Her crime was doubly heinous. By killing the only son, she had in all probability put an end to the lineage. Gertrude was old for childbearing, and no noblewoman in her right mind would marry Armin, the heir-presumptive.

If she were captured, her punishment would be a frightful one, a drawn-out agony from which she’d cry aloud for death to release her. Like her friend Kataryna, who refused to yield her virtue to the Duke’s agent: burned as a witch at his orders. Or Venno the herdsman, styled ‘Lackwit’, accused on the evidence of a two-headed lamb of committing unnatural acts with his flock: strung up, castrated and disembowelled.

Was it not fitting that she should die by the hand that had worked such terrible vengeance on a heedless child? It would be a kind of atonement. She still had half the poison left, and Manfred’s death had to all appearances been an easy one. If her life was forfeit, how much better to slip painlessly away, the sweetness of honey on her tongue…

No. You had but one life, and it was your duty to live it to the full. Anything else was cowardice. Existence was harsh and brutal, death sudden and cruel, ‘justice’ not only blind but capricious. To augment your life, it might become necessary to cut short another’s…

Revolving these thoughts in her mind, she found herself before her home village: the sun brushing the horizon, blazing orange, as she approached the outlying buildings. With a start, she realized she had made no plans whatever. Kicking herself mentally for lack of foresight, she backed into the long shadows to repair her omission.

She could stay here safely only one night. Manfred would be missed at the evening meal. Her absence was expected, and would not immediately be associated with his. But Beatrix was known to be her friend, and would be questioned. A timid girl, she’d spill all she knew, or guessed. Bloodhounds would find Manfred within an hour of dawn. Then, her village was the first place her pursuers would look.

Even tonight, if she went to her parents she’d have to give an explanation. Experience had taught her that lies were best kept close to the truth, but when the truth was that she was a murderess and a poisoner, that was many bridges too far.

Only two options presented themselves: instant flight, or an attempt to enlist Robert’s help. The latter would be a gamble, but she’d risked much already; why not risk all? Fortune favoured the bold. As dusk fell, she slipped into a barn adjacent to a deserted cottage, not far from his father’s house.

The musty smell of rodent infestation greeted her, though agricultural odours – cow manure and such – were absent. Robert, she thought, hard. Come to me. I am near and I need you beside me. Come, my love: repeating the words like a prayer, though she had no faith in prayers, devices invented by fat priests to keep ignorant people servile.

Time, snail-like, crept past. Would Robert somehow divine her crime and refuse to help her, even to meet her? Was she an outcast, condemned to wander the world alone, childless in her turn? A just punishment, perhaps.

Full night was approaching when a shadowy figure appeared in the lane. Could it be…?

It was. Probably on an expedition to some village girl’s bed, but she could still prevail.

“Psst!” she hissed as he came within earshot.

He stopped dead, head cocked, listening. She hissed again, and this time he caught the direction of the sound. Drawing his sword, he approached the barn with cautious steps.

She shrugged off her cloak and showed herself, a slight but womanly figure in her plain gown.

Robert’s jaw dropped. “Eve! Or is it…?” He made the sign to ward off spirits.

“It is. I’m not a ghost. Robert, I hoped to meet you…”

“I thought you to be at the manor, as governess for the son and heir. What the Devil are you doing in Andras’ barn?”

“I was dismissed.” But that was no adequate explanation. “Not for any fault of mine. And –” her voice caught “– I’ve killed him – Manfred, the son. It was he who had me turned away, and I revenged myself.” Her voice rose. “Oh, what have I done? Help me, Robert, I beg you…”

“Sh-h, you’ll be heard. You killed Manfred? How?”

“I poisoned him. He lies dead in the forest.”

“Lord Aldwin will be livid with rage. He’ll have you hunted down as soon as the truth is discovered.” He thought. “I can take you to the ford on Father’s mare, see you across and safe on the other side. That will throw Aldwin’s hounds off the scent. You can disappear into the next town you come to. You’ll make out. You’re a clever woman, not to mention a pretty one.”

Hope sprang up at his last words. “Robert, would you do even more than that for me? I’ve always admired you. I wanted you to notice me, to desire me, to take me as your lawful woman. But what had I to offer the son of a thriving merchant?” Now for it. “You have brains and initiative. You deserve a wider stage than this dog-hole. When I try to escape, will you come with me?”

He rubbed his chin, looking everywhere but at her. She had the wit to keep silent, fighting down her urge to throw herself, pleading, at his feet.

The sound of a sword being sheathed broke into her reverie. Then he spoke.

“Eve, you’re cleverer than I gave you credit for. Your thoughts and mine run together. I’ve long known that I cannot make a worthwhile life if I stay here, but I’ve been too cowardly to take the decision.”

“You’re no coward, Robert. You’re a man whose mind was in conflict, who only needed a friend to help you see your way.”

“You’re right, as I think you always are. You have done me a great service. How can I repay you?”

Eve took a deep breath. “By making me your wife, your life’s partner.”

He hesitated a bare second. “Yes, I’ll gladly do that. But we have no priest.”

“We’ll marry in the old way, then.”

“Agreed. Here’s my plan. I’ll take Father’s horse, as I said. At the first stables after the ford, I’ll send it back with a groom, and hire horses to carry us onward. I have a little money saved.”

“So do I. Lady Gertrude gave me ten ducats, and I have the boy’s purse too.”

“I know three of like mind, who will follow me. There’s safety in numbers, and four men can do what one cannot.”

Fear pricked her. “You’re not thinking of turning robber? I pray you –”

His voice hardened. “By the Black God, no. What do you take me for? The men I mean are honest fellows, not bandits. If we can’t prosper by fair means, we don’t deserve the name of free men.”

She squirmed with embarrassment, glad Robert couldn’t see her burning cheeks. “Forgive me, Robert, I spoke without thought. I trust you, implicitly. And I’m yours, for ever and ever.” She half-ran the few steps separating them. Sensing her movement, he opened his arms.

When they broke, she spoke carefully. “One thing you must know, I’m not a virgin. Lord Aldwin’s brother used to… A servant girl doesn’t have the option of refusing. Will you still take me after Armin has defiled me?”

“It’s no matter. I can’t claim purity myself.” I should say not: Robert’s exploits with the local girls were legendary. “But from this moment on, I vow…”

“From this moment on, everything is new. We are new. Say the words, Robert.”

He took her two hands in his. “I shall guard your life as my own.”

“I shall guard your life as my own,” she repeated.

“May I be struck dead if ever I betray your trust in me.”

“May I be struck dead likewise.”

“We should exchange rings, but that will have to wait,” he said. “I wasn’t expecting this to happen when I came out this evening.”

“Nor was I.” Though I was hoping. Her voice became breathy with emotion. “Take me now, Robert, and seal it. We can lie on my cloak.”

#

At the moment of his release, she cried out with joy and fulfilment, oblivious to the discomfort of their makeshift bed. But that made itself felt soon enough, and they got to their feet.

Eve spoke lightly, as to one with whom intimacy was natural. “You realize you’ve married a poisoner, the worst kind of woman there is?”

“I married a woman of strength and determination. A beautiful one, too. I’m proud of my bargain.”

She buried her face in his neck. “So am I.”

They stood entwined for long minutes. Then Robert’s voice broke the spell. “Now, we must be practical. I’ll rouse Ralf and the others who are to be our companions, and explain my urgency. Then I’ll slip home and get traveling cloaks and flasks of water and wine, saddle Athena, and lead her here. You can ride in front of me. We’ll meet the others on the east road. At the next village after the ford, we’ll make better arrangements. Now, will you feel safe on a night ride like this?”

“I’d feel safe anywhere with you beside me.”

“Together, we need fear nothing.” A pale half-moon had risen, and the tenderness in his look made her pulse quicken, her breathing grow shallow.

“Stay in the barn,” he added. “I’ll be gone less than an hour.”

“I wish you speed and safety, my love. My only love.”

A final swift embrace, and he was gone. From the doorway, she watched his striding figure recede, turn a corner and vanish.

Left alone, she speculated. The coming days might be equally eventful, but soon they’d be free to live the lives of their choice.

What might the future hold? Fit, resourceful, hard-working young men would be welcome in many situations. Perhaps a manor where the lord was elderly and unable to defend his territory? It would be natural for Robert to succeed him. Then, the king cared not a fig for minor skirmishes in the Eastern Marches. They might add to their possessions by conquest. Or war might descend on the country, and the king call all able-bodied men to arms. At the head of a stalwart band, Robert might distinguish himself, gaining royal recognition: a barony, a viscountcy? As a noble, he might shine in the king’s councils, unlettered as he was: his native wit, aided by her sage advice, carrying him to eminence. Their sons would bring dowered brides to enrich their establishment, their daughters marry noblemen and cement dynastic alliances. The chances were good that she would pass her days in dignity and comfort, and die a duchess.